New Documentary Evidence!

The following is an excerpt from my new book on Blackbeard the pirate, showing the kind of world that he lived in, as dangerous and exotic as it may be. This book was prompted by my discovery of documentary evidence showing the family of Edward Theach of Spanish Town, Jamaica. This extraordinary find breathes life into a 300-year old legend that most historians assumed was played out. We never thought that we would find anything new on the infamous pirate of the “Golden Age of Piracy.”

|

| Teaser… |

This excerpt details the piratical devolution of the Bahama Islands, the future home of pirates in the “Golden Age,” calling themselves the “Flying Gang.” Historian Colin Woodard called the ultimate gathering there in 1716-1718 the “Republic of Pirates.” Many of these pirates had inhabited those islands for generations. Some had come there from all parts of the Caribbean. Few of us know that the Bahamas was a sister proprietary colony of the same Lords Proprietors to which King Charles II had given Carolina. We seldom get the chance to realize that proprietorships, or privatized colonies, were the ultimate reason for the degradation and neglect that turned the Bahamas and other colonies like them, including North Carolina, into havens for pirates.

Three hundred years later, we are perhaps forgetting the lessons of history and recreating the anti-government, “corporate” or monarchial rule of the Stuarts, where privilege trumped ability and power suppressed intellect. Enough with the politics… on to the history and pirates! May the wind be at yer backs! Yo Ho!

——————–

From Chapter 2: In the Swamps of the Spanish Main…

…

Vice Admiralty judge and Chief Justice of the Bahamas, Thomas Walker had a most interesting history. Moreover, that history is directly linked to the Fairfaxes, also connected with the United States’ first president, General George Washington. “Suspicions are that Anne Fairfax, Mount Vernon’s first mistress and the wife of Lawrence Washington, the President’s brother,” tell researchers, “was a woman of colour whose mother was born in the Bahamas.” There have been rumors of African blood in that line that descend from Thomas Walker, rumors that an attempt had been made to hide:

- Despite the importance of the Fairfaxes to George Washington’s formative years as a young man, the question of the Negro blood of those in this family who were closest to Washington has never been fully explored. True, a small number of the first President’s biographers have broached the topic, but even these have treated it as nothing more than an interesting rumor. Of any number of scholars whose attitudes on race might have contributed to this omission, the most obvious culprit is Edward D. Neill. And it is his edition of the Fairfax papers published in 1868 which provides us with a smoking gun. Among the letters he transcribed was one which, if it had been printed in its entirety, would have prevented any doubt about the ethnic mix of this particular side of the Fairfax family.

Neill compiled the Fairfax papers at a time when race would have been a serious issue in the United States and he fell prey to a social resentment of African heritage in that time.

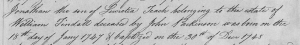

Col. William Fairfax served as chief justice with Walker and acting governor of the Bahamas immediately after Woodes Rogers and married Sarah Walker (b. 1700), Thomas’ daughter. This began the speculation because Thomas Walker’s wife was probably of African heritage. According to the church records from Jamaica that also reveal Blackbeard’s family, these unions were not uncommon in the West Indies and mainland America at the time, including in Blackbeard’s own family. African heritage truly became problematic after the United States gained its independence from Great Britain and especially after the Civil War.

Thomas Walker began his career under Read Elding, former governor of the Bahamas from 1699 to 1701. Elding had been the deputy-governor under Gov. Nicholas Webb and succeeded to that office by virtue of Webb’s death. Elding was himself of African and European mixed blood. He hailed from Boston, Massachusetts where he married Hannah Pemberton in 1695. Walker became Judge of the High Court of Admiralty for the Bahamas on November 4, 1700, appointed by the Hon. Perient Trott, father of former Bahamas governor, Nicholas Trott. Walker noted soon afterward, that part of his duties were “to pay unto the King the tenths of all wrecks and other matters arising to the King by virtue” of his commission as Admiralty judge. Wrecking was a profitable venture in the Bahamas, with over 700 islands enmeshed in shallow and dangerous shoal waters.

|

| New Providence Island in the Bahamas |

Walker’s relationship with Gov. Read Elding, the “assumed Deputy Governor of the Bahamies,” as he referred to him, was tenuous. Elding opted for that tenth to go to the proprietors and not the king. Walker, like his friend, customs collector John Graves, both not fans of proprietaries, disagreed. As he warned in summer 1701, “the Deputy Governor is resolved to take and receive for the Lords Proprietors, and he being too strong and potent will overcome us, [unless] we have further direction and protection from England.”

Walker’s fiery situation with Elding had grown worse. He related that his attempts to collect revenues for the king had angered Elding. He accused that “The Dep. Governor has lately attempted to murder me and the Vice-Admiral.” Furthermore, the Spanish had lately threatened to attack Nassau and tear down the fort because they feared attacks from the English. A precarious situation presented Walker with little choice, as he saw it. “I have imbarqued upon a vessel of my own well victualled and manned for the King’s service,” he wrote, “and am in my passage to Virginia to Governor Nicholson, there to crave the aid and assistance of a man of war.”

Walker landed in the Albemarle of North Carolina and sent his request from there, through the Dismal swamp roads, to Nicholson on April 24th. He later related that Elding “privately supplied known pirates about those Islands with liquors and refreshment, and underhand hath taken their ill gotten money for the same, and enriched himself thereby.”

A growing presence of pirates may have prompted the belligerent Spanish reaction. Still, Walker himself supplied perhaps the real reason the Spanish resented English presence in the Bahamas: “The port of Providence may be used for H.M. ships not over 17 foot draught, whence they may run to the edge of the Gulf, to attack the Spanish Plate Fleet.” The “official” English West Indian agenda had been, since the early seventeenth century, stealing or pirating Spanish gold and silver. They considered all Englishmen to be pirates. Queen Anne’s War had not yet begun, either. That was still two years away.

Gov. Read Elding had been removed from his office and arrested; Walker then returned. Still, in October 1701, nothing short of a revolution occurred in the Bahamas, led by Elding and many of his supporters, apparently a growing majority in the islands. A new governor, Elias Haskett, 33-year-old son of Stephen and Elizabeth Haskett of Salem, Massachusetts, had been appointed, and subsequently deposed. Haskett’s politics also favored the king, though he was a bit rough around the edges. Walker relates:

- Col. Read Elding was a prisoner by a mittimus for piracy and dealing with pirates, and several other high crimes and misdemeanours, but to free himself he came first to the Governor, pretending to visit him. Immediately the people with arms followed him into the Governor’s house, and seized the Governor. Then Elding headed them and carried the Governor into the Fort, prisoner, when two great guns were fired, whereupon the people, as in the nature of an alarm, came from their own homes with their arms to the Fort, where being in a body, the said Elding at the head of them, first motioned for the people to vote Thomas Walker, Judge of the Admiralty, to be put in irons. All the people with one consent said, no irons. Then Elding motioned for irons to be put upon the Governor. The people answered, Irons upon the Governor, wch. according were put upon his legs, were strong and heavy ones.

Walker was trapped. He dared not make trouble for the proprietary men, for he had a family and a daughter only a year old. To get word of what happened to other loyal governments, though, he hollowed an apple and placed a note inside, then used small metal pins to hold it together. He passed this apple amongst a “half bitt’s worth” to Barbados councilman William Davie, master of the Sloop James City, who had loaded with salt and prepared to depart. It just so happened that, Davie, on his way from New Providence to Virginia, was fired upon and plundered by pirates. Still, he made it to Virginia by November and delivered Walker’s message. Still, the most fantastic events of the Bahamian Rebellion were yet to come.

Capt. John Crawford delivered Haskett to New York in the Katherine and was subsequently arrested for treason upon Haskett’s quick accusation. In New York, Haskett successfully argued against his opponents, including John Graves who he alleged “forced me on board a small ketch, where they put me in irons, keeping my wife and sister still prisoners… In which ketch I continued untill I came to New York, but most barbarously treated by Graves, who did contrive severall times to murder me.” The Chief Justice of New York declared the actions against Gov. Haskett “amount to High Treason.” Bahamas’ collector John Graves and naval officer Roger Prideaux were both jailed and held for five months, despite the evidence that they sent with the deposed governor. Graves and Prideaux petitioned that they were “maliciously and falsely charged with High Treason and Rebellion, grounded on an information full of absurdities and obscure and general charges,” all lies of Elias Hasket. Crawford, tried for piracy in Admiralty proceedings in New York, was acquitted, but he was still held for the act of treason.

Graves, ironically also a king’s man, alleged that Haskett tried to get rid of the documentary evidence. On December 24th, Graves called as a witness one “Downing, a mariner in the vessel they arrived in.” Downing testified “that Hasket had offered him a considerable reward on his arrival here, if he would throw a box Mr. Graves’ papers were in overboard, and give Hasket the largest packet therein.” Downing refused.

Damning evidence, however, was collected by the people of New Providence and sent in those papers with John Graves, which Haskett was unsuccessful at having destroyed. In particular was the testimony of William Spatcher, master of Robert and Martha. On November 7th, Spatcher testified that Haskett gave him written orders to cut firewood on some of the Bahama Islands. Spatcher attested to this being merely a ruse to trade with the French at Hispaniola. Spatcher said that he was told to cut brazilleta wood and carry it to trade for “French commodities, as alamode silks particularly ordered, to be landed privately, short of” Providence harbor, clandestinely. “So desire you to send me in English a letter,” Haskett wrote to the French governor, “by reason no person shall see it but myself, what will sell with you and the prices you will take the goods at, and also what you can furnish me with and at what rates.” Naval officer Roger Prideaux confirmed the note having been written by Gov. Haskett. A written letter would be the most damaging evidence, like the letter from North Carolina’s Chief Justice Tobias Knight found on the body of Edward Theach when he was killed in 1718.

There were also allegations to the tyrannical activities of Bahamas’ six-month governor. Supposedly, he had caused Capt. John Warren, a privateer out of New Providence to capture Seaflower, a sloop intending to take in salt at Turk’s Island. Allegedly, Haskett wanted to know whether the master of Seaflower had been doing so under commission from the Lords Proprietors [as opposed to the king] and he “threatning withall that if they did not agree in their answers he would cut off their ears.” Other accusations made that day against Haskett included one complaint from Seaman John Caverly. Caverly said that Haskett accused him of trying to illegally rake salt and cut wood. Caverly alleged that Haskett “commanded a Negroe to put a halter about the said Caverly’s neck.”

…

|

| “The Wreckers” 1791 |

The governor gave his own account of the rebellion by the Bahamians. His version sounded much less civilized. Haskett provided more detail that implicated others, including Customs Collector John Graves. “James Crawford, John Graves, Read Elding and Ellis Lightwood with some other confederates,” he said, “did combine and seize and remove the Governor from his Government.” Still, the manner of their actions, as Haskett alleged, was far from civil. Haskett testified that:

- … with swords, pistols and other arms went to the Governor’s House in Nassau, where he then was, and fired into it, at him, but the shot missing him, one of the Confederates was wounded, by which means they left off firing and betook themselves to their swords, with which they seized the Governor, wounded him in several places and immediately carried him away to the Fort, and there loaded with irons and confined him a close prisoner, and the same night drove his wife, sister and the rest of his family into the woods, and seized upon and took or shared amongst them all his gold, silver, household goods, plate, furniture, merchandize, Commission, Instructions, Bonds, Bills, Mortgages and whatever else belonged to him to the value of several thousand pounds, part of which was the King’s money and Lords Proprietors’.

Haskett made strong defense to Gov. John Nanfan and the court. That defense shows either an active imagination or something about the actual state of Bahamian society at the turn of century. He alleged that the people of the island framed him and Spatcher was coerced into a confession. He repeated that the confederates stole his property, worth £5,585. The Bahamians themselves, he said, were little better than pirates. Haskett also alleged that Elding and his men had fired on a vessel from Jamaica and pirated the goods. Samuel Thrift, he said had chased down a brigantine from New York. One Curtis, he told, at the Island Maraguana, left “a vessel burnt down to the water and near 20 men dead on the shore.” The most astonishing testimony concerned Elding’s ship captain:

- About a month before I was seized, a sloop of Elding’s, Symms, a negro, commander, came into port after about 4 months’ voyage among the Islands, who in her return found an English vessel that had lost her way, and whose men were ready to starve, upon which they plundered her, murthered the surgeon, and set the rest of the men adrift in a small boat and then fire to the vessel. All which appeared to me upon the oath of William Gibbons, one of the said sloop’s crew, as also that Simms was the person that murdered the surgeon. Simms told me that the surgeon told him that he had undergone a great many hardships and was very ill, and desired that he would put an end to his life, and that thereupon out of charity he took a broad axe and cut off his head.

Unfortunately, the records contained no further reports and alleged no outcome to these quite remarkable proceedings. Graves returned to the Bahamas where he would continue making pleas to the Crown to invalidate the proprietors’ charter for the islands. Back in England, Haskett’s creditors related that he had “absconded to the Bahamas” to escape them in the first place. Michael Craton tells that “Having fixed a rendezvous at the Rummer Tavern, Graceschurch Street, he had gone to Portsmouth instead.” A bailiff sent in pursuit was repelled with firearms and Haskett fled England again. Still, having settled in St. Margaret Westminster, Middlesex in 1720, he became embroiled in further legal matters concerning the former Bahamian governor, then London merchant, Nicholas Trott.

Just as Edward Randolph, Thomas Walker, John Graves, Francis Nicholson, and other administrators worked to have the proprietary colonies assumed by the Crown government, war began. War with France and Spain would finish the ailing Bahamas and reduce them to a population of mere stragglers on the edge of the woods, fighting like guerrilla soldiers from modern-day Nicaragua.

As the Haskett affair was playing out in New York, in February 1702, a draft proposal had been prepared for the surrendering of the proprietaries, East and West New Jersey to the Crown. King Charles II had originally given the Jerseys to his brother James after the English Civil War and the subsequent Dutch wars. He, in turn gave them to two of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, Sir George Carteret and Lord Berkeley of Stratton. Private misrule had become evident in all of these proprietary possessions, palpable in the Board’s investigations into “requiring information relating to the conduct of Proprietary Governments,” particularly the Jerseys in 1702.

On March 2, 1702, Anne, daughter of James II, succeeded William III of Orange, who had died from pneumonia complications after falling from his horse and breaking his collarbone. William’s Whig reign, however, had marked the beginning of a transition from the personal or privatized rule of the Stuarts’s supreme monarchy to a more parliament-centered or government-checked monarchy of the Hanoverians. Thus, it invigorated peripheral effects in the rest of the empire, including America with a tendency toward eradication of corrupt private colony charters, former indulgences of King Charles II. The Board of Trade and Plantations, formerly Lords of Trade and Plantations and the purview of the king’s Privy Council, was made a separate body independent of the executive in 1696. This reduced possible corruption.

In April, the Board of Trade sent the queen a synopsis of the American colonies in her realm. In it, they included that both the Jerseys and Pennsylvania are “without fortifications” and unable to defend themselves. Furthermore, “North and South Carolina are [also] under Proprietors, who do not take due care to put that country into a state of defence.” They also suggested that the proprietors be encouraged to take care of their possession of the Bahamas for their preservation from an enemy, notably Spain. This, like most endeavors, they never accomplished. Furthermore, all they had ever done was to show favor to their questionable friends by granting them favors, governorships… as King Charles II had done for them. Obviously, they never fully investigated Haskett or they would not have hired him.

Gov. Haskett made the fourth corrupt governor in a row, perhaps more, beginning with the notorious Nicholas Trott. Trott married Ann Amy and later claimed a Carolina proprietorship as well on the death of his father-in-law, Thomas Amy. He was refused for obvious reasons. Several representatives in the Bahamas, including several proprietors’ deputies and Read Elding, wrote to the proprietors late in March. They elaborated on and complained of Haskett’s probable acquittal:

- The unparalleled villainyes of your Lordships’ late Governor Haskett have been so intolerably oppressive beyond all expression that for the preservation of our lives and fortunes, we were forced to suppress him, of which we gave your Lordships an account by the vessel hired by the country to carry him home to England to answer the sundry barbarous crimes we have to allege against him, [but] that in the proceeding of their voyage putting into New York he thereby bribing of the Master or sailors made his escape.

The rebels or pirates who abused Gov. Haskett favored proprietors while most of the administrators of the island did not. Of course, many of them believed that the proprietors would favor them and took more of their interests to heart than the king. Moreover, they were freer to engage in illegal activities under the negligent proprietors, paying little attention to anything that happened on the islands. Most everyone agreed: the proprietors had to go. Still, the proprietors, in 1702, did not lose their colony. The coming war distracted officials. Another sixteen years would pass before that happened.

Gov. Sir William Beeston became the next royal executive for Jamaica. An act “for the restraining and punishing Privateers and Pirates” passed as well. Soon afterward, the Secretary of State Earl of Nottingham notified Beeston of the beginning of the war with France and Spain. The Lords Proprietors sent word directly to their colony “to annoy the subjects of France and Spain, and to preserve and defend our Colony.” This, inhabitants would have to accomplish without funding or other aid from the proprietors, of course. Queen Anne’s War had begun.

The Bahama Islands were almost immediately devastated, which did not require much effort. September 17, 1703, John Moore of Carolina, in Pennsylvania with Robert Quarry, sent a letter to the Board informing them of New Providence’s final destruction. “Spaniards and French… had lately attacked the Bahama Islands, destroyed Providence, putting all the men to the sword, and designing to burn the women had not the humanity of one of the French officers interposed.” Rescuers “brought off about 80 of the people (most women) with them, and in their passage took a Spanish ship about 150 tuns laden with cocoa and other valuable goods.” Acting-governor Lightwood abandoned his post as well. Moore clearly blamed private rule of the proprietors for the destruction and mayhem on the Bahamas. He said “[Spain and France] had this notion that those Islands were out of the Queen’s protection and independent from ye Crown (one of the ill effects of [proprietary] Charters).”

Edward Birch of Carolina deserves little mention as the next governor of the Bahamas, appointed in 1702. The destruction of the Bahamas, however, occurred before his arrival, brought over by John Graves from Charles Town on January 1, 1704. He was to replace the acting and absent “proprietary president” Lightwood. Birch had returned to Carolina by June.

As if emulating the destruction of the nearby Bahama Islands by their mutual enemies, a dreadful fire struck Port Royal on Jamaica, only eleven years after the devastating earthquake of 1692. The chief seat of trade was moved to Kingston across the bay and refugees from Port Royal were being taken there. Then, the intent was to abandon the strategically-placed Port Royal, just as proprietary neglect had abandoned the strategically-placed Bahamas. The war in the West Indies had not begun well for the English.

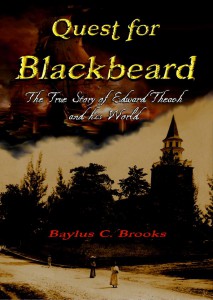

Capt. Robert Holden, master of the Granville had sailed for the Bahamas to search for wrecks, as he held a patent from the Proprietors to look after the “whale fishings and wrecks in those parts.” Disappointed in that search, he was raking salt on Exuma in early May 1704. There, he was chased by a French ship and privateer, both running English colors to fool him. The ship had 16 guns and 50 men, the privateer had but 4 guns and 60 men. Holden was taken that day. He later visited several of the islands in that chain, but never made it to New Providence, as it was destroyed and the fort in ruin.

The Bahamas were vital to the war effort and their dilapidated situation had grown desperate. The Board wrote the Queen in June 1706 to express that “We are humbly of opinion that the immediate Government of those Islands [Bahamas] shou’d be resumed into the Crown.” They asserted that the “present defenceless state of those Islands hath been through the default and neglect of the Proprietors.” Still, the proprietors insisted upon keeping the Bahamas. The wreck-hunting mariner Capt. Robert Holden, a two-decade veteran of the troublesome Albemarle in North Carolina and having knowledge of the Bahama Islands, was their choice for its next governor.

Collector John Graves chose to defend his home, despite the proprietors. For him, they were negligent of such a strategically-placed resource even in a time of war when England needed it most. He addressed the Board in December 1706. He told them in “December last there was about 27 families remaining on the Island of Providence and about 4 or 500 inhabitants scattered in the other islands.” Graves assured that they were not necessarily defenseless, with “about 14 sloops at Providence.” Graves needed a hundred soldiers with officers and provisions. With those, “he did not doubt but that in a little time, with the assistance of the inhabitants who may be all summoned to Providence, they would be able to defend themselves against the Spaniards,” and repair the fort.

John Graves, however, not at all in favor of the proprietors, told the Board that he “had heard that Mr. Archdale, one of the proprietors of Carolina, had given a bad character of Mr. Holden.” Archdale later informed them that he found Holden in jail when he first arrived in Carolina, but realized that he had been placed there by John Culpeper’s rebels in the 1670s. He, therefore, had no problem with Holden. In fact, most of the proprietors were enamored with their old friend. Archdale also agreed that the Bahamas needed a great deal of repairs for which he doubted he and the other the proprietors would be willing to pay.

Capt. Samuel Chadwell of the Flying-Horse sloop, understanding that the proprietors considered Holden as their governor for the Bahamas, thought to acquaint him with the colony’s current situation as of October 1707. The inhabitants there were “about 600 (300 freemen),” he said, dwelling upon Eleuthera, Cat Island, Little and Great Exuma, Providence Island, and others. They live scattered, in little huts, ready to secure themselves in the woods when attacked.

Their trade consisted chiefly of braziletta-wood, tortoise-shell, hunting for wrecks, raking salt, and staying alive. Most trade came from Jamaica, some from Curacao, St. Thomas, Carolina, and Bermuda for liquor and dry goods. About twenty vessels trade there in a year, Chadwell said, generally of abt. 40 tons burthen, which load with salt and wood. Exuma and Eleuthera are the main places for trade since Nassau was burnt. Only about three houses remain there. He assured Holden that the fort was strong, but the houses within it were burnt. Only about twenty men were left on the whole island. Woodwork and iron will be the greatest expense to secure the Fort, he said. The people survived by using guerrilla tactics against their attackers, using the natural cover of the woods.

Chadwell described the harbors. Vessels of about 300 tons could trade at New Providence. Ryall Harbor could accommodate 100 tons. Harbor Island had about three fathom of water and could take 200 tons, although somewhat shoal-ridden within the harbor. Hockin Island could accommodate 70 tons.

There were about a dozen small vessels there, some about 16 tons. They fitted out a privateer of about 20 tons the past January. Capt. Thomas Walker as commander went upon the coast of Cuba with thirty-five men, took about five small vessels, and made about £50 per man. The people of the Bahamas held out the best that they could, living on the front line in a war zone, without aid.

Chadwell supplicated and practically begged the proprietors for any money or supplies that they might send. He assured Holden that the people would flourish if a new government were settled there; but, at present, their situation declined. Chadwell yet blamed the Crown for this. His words, though, belied the truth. “They are very desireous of a Governor, and wonders ye Lds. Propriators sends [them] not one,” he said, “they seem devoted to ye Lds. Propriators and loves [them], for their great privilidges.” These poor people waited in vain upon unsympathetic “gentlemen” owners in London, 3,000 miles away and safe. There was no profit in the Bahamas. The proprietors would not help.

For whatever reason, probably money and the sad state of the islands’ present condition, Robert Holden never arrived in the Bahamas. He appears in London by the end of 1707 when he wrote a description of Carolina for the Proprietors. Afterwards, however, he was not heard from again but briefly. He did not attend the meeting of the Bahama residents with their council, Mr. Ayloff, and the proprietors with theirs, Mr. Phipps, in London at the Board in Whitehall in December 1708. The Board offered that “they need not unnecessarily take up time in setting forth the advantage of the Bahama Islands to this kingdom, or the ill consequence it might be were they in the possession of the enemy, their lordships being fully apprized thereof.”

At that meeting, Mr. Phipps defended the proprietors by saying that “the revenue of the said islands was about 800l. a year, which their lordships have wholly applied to the defence thereof.” Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper spoke for the proprietors at the accusation that they did not support the Bahamas. He only referred to the profit of the colony being no benefit to them. Robert Holden, Phipps said, told him that the “Lords Proprietors did not intend to send over any stores of war; but that he intended to carry over a small quantity himself for sale.” Obviously, profit trumped national defense. The Board easily recommended, again, the resumption of the proprietors’ charter and, still, they argued to keep it, despite the danger that their private profiteering posed for Britain’s wartime affairs in the West Indies. Human lives never figured into the economic equation. The Bahamas, under private ownership, created a perfect environment for pirates.

Even by 1708, according to John Oldmixon, Bahamian inhabitants were “living a lewd licentious Sort of Life, they were impatient under Government.” If Elias Haskett was accurate in his complaints about these allegedly piratical islanders, they were certainly pirates by 1708. Oldmixon also commented on their subsistence activity of “wrecking,” or a “Scandal, but it is most notorious, that the inhabitants looked upon every Thing they could get out of a Cast-away Ship as their own.” This activity they also share with the North Carolina Outer Banks’ early residents. Then again, the Carolinas were also retained by private owners.

From its proximity to Spanish possessions of Florida and Cuba and also adjacent to the Straits of Florida where all shipping to the eastern seaboard of America or Europe must pass to follow the currents and trade winds, the Bahamas created essentially a “toll gate” for all fleets that must pass right by them. This was possibly the most important tactical locale in the West Indies and vital to Britain’s war efforts. Anyone who wished to raid Spanish gold and silver shipments would find the Bahamas ideal with 700 islands to choose from for careening, hiding, obtaining fresh water and fruit, and other supplies. It contained shallow waters with deep channels only known to local pilots. Pirates could hide there and be assured that no large vessels would dare follow them within the intricate and deadly maze. Colin Woodard reassured that, “The Bahamas, as every Jamaican knew, was a perfect buccaneering base.”

The old fort at Nassau, however, built and supplied by Gov. Nicholas Trott, had crumbled to ruin by the beginning of Queen Anne’s War in 1702. The Bahamas was never able to mount any real defense or offense during that war. The sea had undermined the wall of Fort Nassau and it had plunged into the water. No cannon remained that were not spiked by enemy forces. Only twelve families persisted out of 150 that used to reside there. The Bahamas, the sentinel of the British West Indies, was in tatters. The government had disappeared. The few residents that still lived on, including the former Admiralty Judge and Chief Justice Thomas Walker and his family, Customs Collector John Graves, and other older residents resisted the urge to leave their home. Perhaps they refused to abandon the colony for the sake of their country. Perhaps they possessed more patriotism than the proprietors were willing to express. Still, the Bahamas had become a haven for pirates.

King Charles II behaved no differently than Queen Elizabeth or the Lords Proprietors when it came to furthering piracy. By the early eighteenth century, fellow Englishmen had to deal with the irresponsible atmosphere that they created in America. Their selfish ideology differed little from merchant-pirates who now infested the Caribbean. Furthermore, few of them and their many lackluster officials had intentions more noble than pirates of the “Golden Age.” Claire Jowitt stated that, whereas earlier, “the margin between licit and illicit activities at sea was fluid, before the more definite criminalization that ‘piracy’ came to possess in the Golden Age of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.”

Who really were the greatest pirates? Were they the corporate shills that raided other businesses and cared more for their profit and possessions than for their country’s security and the safety of its people? Or were they the brigands who raided other ships and spread the wealth at reasonable prices?Who could really tell the difference?

In our desire to dissect our past from the deeds of careless profiteering in the Caribbean, reinventing the history of America as we do, we have lost the meaning and context for piracy in the West Indies. In the process, we have also lost ourselves. We can attempt to recapture our past, to clear it from the rhetoric… and so begins the quest in the oddest of places… the quest for Blackbeard’s true being amidst his truly decadent world.